10/10/2024

While filming in Beirut, we were very reckless: even though we had an armed guard, we almost got killed

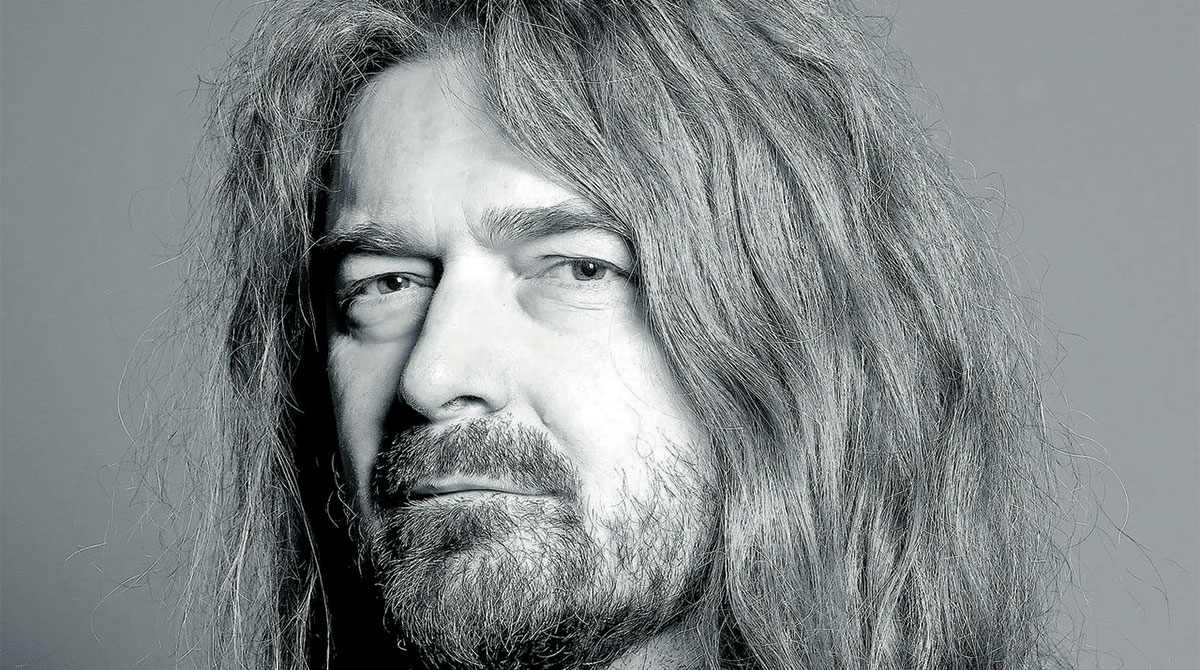

The producer and one of the founders of the Mediterranean Film Festival, Robert Bubalo, has mainly dealt with rock music in his documentary films so far, being the author of "Lost Button", a film about the drummer of Bijelo dugme Ipe Ivandić, and the only film about rock musician Goran Bare - " Bare". Now he made a breakthrough with the film "Hassan's Wars", which he shot in Lebanon, which was screened in the main program at Dokufest in Prizren in August, and won at the Vukovar Film Festival, in competition with this year's Oscar winner, "20 Days in Mariupol".

The audience at the Mediterranean Film Festival is going to have an opportunity to see your documentary “Hassan’s Wars”. We have waited for it for quite a long time. A decade flew by in the announcements, until your friend Hassan finally "cracked" and allowed you to film his life's destiny. Tell us about your film and why it was so important for you personally to make it?

First of all, Hassan is a big friend of mine. He came to Zagreb from Beirut and I came from Široki Brijeg. I quickly noticed that, despite the famous cultural differences, the two of us actually share a similar spectrum of emotions, hopes, worries, that our worlds are equally shattered due to brutal reality, that our ideals have disappeared because our dreams have been robbed, but also that we love to be hedonists in the same way, to enjoy these remnants of some of our imagined lives and draw the maximum from it. This is a film about a human giant, a man who shook off the negative energy imposed on him from his heart with an infinite strength of spirit, a story about an innocent boy who tapped eggs at Easter with his best friend Tony, who was Christian, and who "choked" on baklava at his place for Bairam, and who separated in the whirlwind of the terrible Lebanese wars and turned their guns on each other, who after ten years, again by some mysterious magic, met and then Tony helped Hassan to get out of Beirut, which was being destroyed by the Israeli air force as it is today, and to arrive in Croatia. It is a story about how he began to learn a different life in Croatia, without anger and revenge, how he became the best Croatian journalist, how he became a great critic of Islamists and how the Croatian police guard him 24 hours a day because of this. The film is uncensored, so there is a lot of political incorrectness, swearing, conversations about killing, but also a lot of spontaneous humour. I believe that we packed it into one rock’n’roll, avantgarde, adventurous, emotional, geopolitical, and yet very personal story.

The film follows your film crew, headed by Hassan, on their way to his hometown, to the former Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in the southern suburbs of Beirut, where he came from. How much was planned? We assume that you started with a certain idea, but how much did you let the film happen on its own?

I will never forget the moment when I stopped with Hassan's wife Ljiljana and the producer in that wonderful Shatila to take a few photos. That's when we walked away from a part of the crew, the cinematographer and the sound engineer, and Hassan, but also from the escort of our armed guards, and wandered into Rehab, the part of Shatila where ISIS and drug gangs settled down. No matter how stupidly we acted, wanting to immortalise ourselves in an incredible environment, in a neighbourhood where neither the Lebanese police, nor the army, not even Hezbollah, let alone cameras from a western country, enter, our guards, the Fatah people, were just as stupid, who crammed in front of the camera and simply ignored the fact that they had to watch out for one part of the team that went astray due to mutual carelessness. Because of this carelessness, we almost lost our lives, and the search for us was documented by the exceptional courage and competence of our cinematographer Bojana Burnać and sound engineer Tomislav Bubalo, my brother, who, despite the radically tense situation, regained his composure and audio recorded everything. But the problem arose after the end of the drama because Hassan, because of his lost nerves, wanted to stop the filming. Basically, our relationship was disrupted then, everything we recorded farther on was not usable. Luckily, we had already filmed most of the materials. And what we filmed was truly fantastic. Many people asked us later how we managed to get out alive. The only logical answer to me is that not even the ISIS members were ready to have three stupid westerners in front of them, so they were still, and we managed to escape in those 20 minutes of hell. Afterwards, we were with the Hezbollah soldiers in Baalbek, who were very cordial, one of their soldiers even made us popcorn.

How did you cope with the challenges of portraying such a difficult and emotionally charged story?

When Hassan read the narration in the editing, which lasted eight months due to the difficult and painstaking translation from Arabic to Croatian, he was deeply emotionally affected, he had a hard time reading, tears stuck in his throat.. I remember that I also cried at one point, for a completely different reason, when I realized that I had 30 hours of material in Arabic and it seemed to me that I would not untangle it for the rest of my life. Basically, I put a lot of effort into editing, I used to dig through the materials at night, compose the story, insert music, and fix something every day and so on indefinitely. Seven days before the end of the editing, when I wanted to improve some things, my son Borna got hurt, so in an ecstasy of anger I sent everything to go to hell and decided that the film was finished. Of course, even without my final beautification, I think we made a great film.

Going back in time certainly caused a lot of mixed feelings for your main character, the trauma of war and a childhood that was far from idyllic. These are the images that he had probably shared with you earlier. But how much of the man you know did you see on the streets of Beirut, and how much of that boy soldier?

Hassan is a Lebanese in Beirut, and Croatian in Zagreb, and it can be seen very well in the film. The Lebanese are more immediate, more direct, they don't try to show some beautified alter ego, but they are what they are, unlike us Croats who always try to give a false image of ourselves. This film helped Hassan to shake off his past, he was actually a deeply wounded man. Not just physically, because he carried a bullet in his head for ten years, but emotionally, he was bleeding all these years until he finally agreed to make this film and until we went through all his traumas together. He joined the PLO when he was 10 and shot in vain at Israeli planes, he was ready to commit a suicide attack, he was completely brainwashed. And now I am looking at a man who is facing his past, with a dead brother, a dead girlfriend, a missing friend, a destroyed childhood, but also the chaos that still reigns in his native Sabra, and I see that a wound lies in every corner of his life. But regardless of all these hard emotions, Hassan is a brilliant joker. The moment in the film when he asks his sister, "Do you remember that I wanted to kill your husband?" describes all the tragicomedy of all these intertwined family relationships.

The film has already received a lot of awards, but apart from the awards, what gave you the greatest satisfaction and how much did this film affect your friendship?

Our friendship also varies, like any good friendship, but it is eternal. And the awards the film won, as well as the great reviews, prove to me that you shouldn't make the so-called festival films, a term I hate, but to return to the initial settings of documentary, that is, to be faithful to reality and let the camera hunt what is happening around you, that is, around the subject of the film.

Is there a new project in preparation, what is currently occupying you?

First of all, I believe that "Hassan" will live for the next year, especially because of the situation in the Middle East in Beirut, which, unfortunately, is in favour of the film. By the way, I am negotiating with Tony Mandich, the vice-president of Atlantic Records for many years and one of the world's most important discographers, to film his life story and thereby to work with his friends Mick Jagger, Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Bon Vox, Eric Clapton...